Natural Language Processing

Natural Language Processing

Automatically processing natural language inputs and producing language outputs is a key component of Artificial General Intelligence. The ambiguities and noise inherent in human communication render traditional symbolic AI techniques ineffective for representing and analysing language data. Recently statistical techniques based on neural networks have achieved a number of remarkable successes in natural language processing leading to a great deal of commercial and academic interest in the field.

We develop computational models of various linguistic phenomena, often with the aim of building practical natural language processing systems.

Our research interests span a broad range of topics in Computational Linguistics and Natural Language Processing. Recent focus areas include:

-

compositional semantics using distributional models

-

deep learning

-

variational Bayesian inference

-

nonparametric Bayesian modelling

-

statistical machine translation and language modelling

Example of a Deep Learning project:

Our goal is to determine the computational and statistical principles responsible for brain function. We seek to understand the role played by different memory and information flow mechanisms.

In simple terms for most chocolate loving fans out there, if you think of the brain as a chocolate cake (something that has very complex smell, taste, texture, but it's just hard to describe in its glorious splendour), what we are trying to do is describe the chocolate cake in terms of a set of ingredients, cooking steps and perhaps a few images. The recipe with pictures is what we refer to as an algorithmic (i.e. recipe) explanation of the chocolate cake. While chocolate cakes are complex and varied, the ingredients and steps to make them tend to be few and common to all of them. There is a bit more to the story, because contrary to what some would endorse, brains are a bit more complex than cakes.

One sound way to understand how the brains of different creatures work, is to build artificial brains that make it possible for us to carry out controlled experiments. By performing experiments, we have a great opportunity to unveil theories of how the brain works. The brains that we build also make predictions that can be verified by neuroscientists or by means of performance on data (e.g. ability to recognize speech, objects, language, etc.).

In our quest to build machines capable of different brain functions, such as image and speech understanding, we have discovered that it is of paramount importance to understand how data in the world shapes the brain. Models that are learned from data are the best at many tasks such as image understanding (e.g., knowing where faces occur in images, recognizing road features in self-driving cars) and speech recognition.

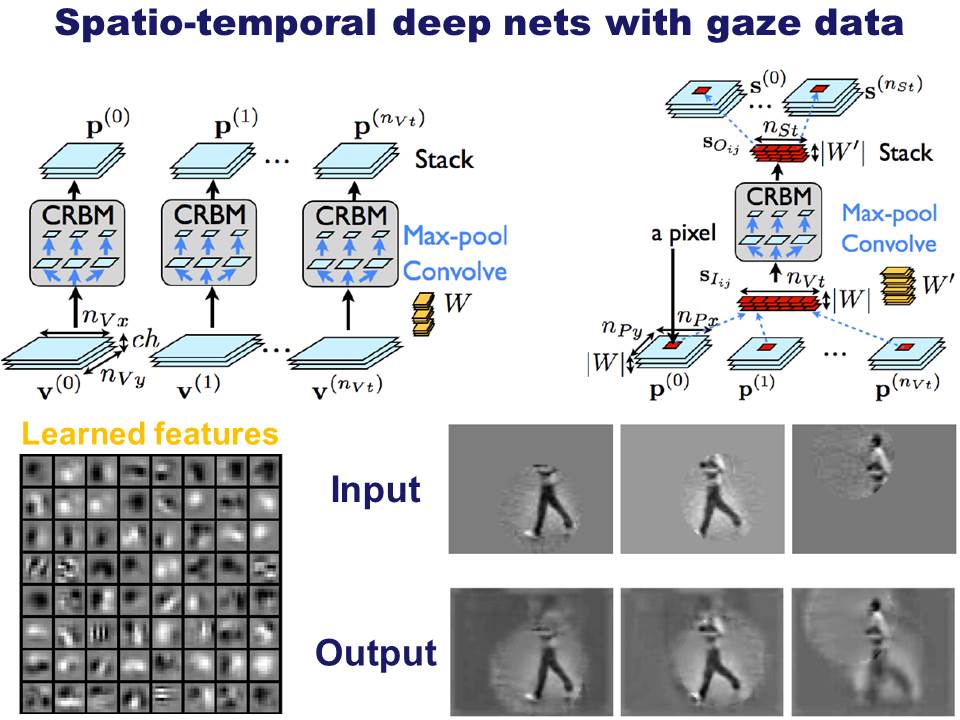

Deep learning models are winning many prediction competitions and are state-of-the-art in image several recognition tasks and speech recognition. Much of the story of deep learning can be told starting with the neuroscience discoveries of Hubel and Wiesel. However, it is also a story of understanding function composition, invariance via nested transformations and lots of data, the statistics of natural signals and why big data sets are needed to capture these, nonparametrics, regularisation, randomisation, max margin training, mapping hard problems in discrete spaces to simpler problems in spaces with smooth embeddings, transfer and multitask learning by sharing embeddings, connections between autocoders-sparse coding-ICA-Ising models-manifold learning; incidentally, the unsupervised methods are not bad, despite the fact that we can extract a bit more predictive juice out of convnets. Deep learning is a rich branch of machine learning.

Our work on deep learning covers foundational theoretical work in the fields of mathematical statistics, logic, learning and algorithms. It also covers a wide range of applications, including object recognition, speech recognition, tracking in HD video, decision making with deep features, imitation learning and reinforcement learning, entertainment games, computational linguistics (question answering, semantic parsing, mapping speech to action, translation, summarization, sentiment analysis) and much more. As an illustrative example of what our models can do, the one presented in this paper is able to interactively predict text as a person types a string on the screen.

In the examples below, the user typed the text in boldface and the model generated the blue text after the “—” symbol automatically. We trained on the LaTeX source of the (excellent) machine learning book of Kevin P. Murphy.

F — or example, consider the form of the exponential family

Fi — gure~\ref{fig:betaPriorPost}(c) shows what happens as the number of heads in the past data.

Figure o — f the data, as follows: \bea\gauss(\mu|\gamma, \lambda(2 \alpha-1))

Figure ou — r conclusions are a convex combination of the prior mean and the constraints

Figure out Bayesian theory we must. Jo — rdan conjugate prior

Figure out Bayesian theory we must. Jos — h Tenenbaum point of the posterior mean is and mode of the

Figure out Bayesian theory we must. Josh agrees. Long live P(\vtheta — |\data)

Deep learning is a vibrant research field at Oxford University. While Phil Blunsom leads this research direction in Computer Science, other folks working in this area at Oxford include Yee Whye Teh, Andrew Zisserman, Andrea Vedaldi, and Karen Simonyan among many others. We have joint reading groups and a lot of fun together.